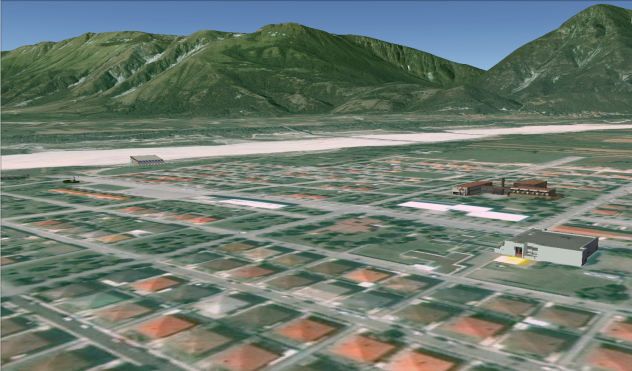

As you can see the Italian school behind mine has its own 3D model, the white building in front does not.

My dad and I are racing south from the Rhineland towards the Alps. It had been years since I had seen them, and their sheer peaks and narrow valleys towered over the castles and villas. We’re headed back just to see it all again, the place where I grew up. Oddly enough we’re making the journey in a small-block Dodge pickup that surprisingly handled the fury of the autobahn well.

My time spent attending “Department of Defense Education Activity” or “DoDEA” schools was probably representative of what suburban public education in the United States looked like. For one thing, my school wasn’t located on a military base. Until the late 1990s, the US-led NATO bases in the northeast region of Italy lacked centralized housing for American personnel beyond non-married GIs. Therefore, nuclear families like mine were dependent upon the local offerings for residence.

In the seemingly pax-Romanic period of the late nineties, my family settled into a small town called Malnisio on the outskirts of Montereale-Valcellina. Serving as a edge to this township was the westerly leg of the Torrente Meduna, a massive dry river-bed nearly a kilometer wide and ten long. At its northernmost point was a dam situated at the foot of Monte Fara, a craggy peak that serves as a gatekeeper to the Dolomites. From a satellite view, the bed’s dry white rocks are clearly visible, making the whole formation look like a large V-shaped scar on the Adriatic Plain. During heavy rainstorms the bed would begin to channel water but it seldom resembled an actual river. My school bus would traverse the nearly kilometer-long bridge spanning the Torrente, west to east toward Maniago and Vajont. Fast forward over decade later and I was finally returning to see what had become of my forgotten school.

Satellite Schools

DoDEA operated three elementary schools for kids living in towns surrounding the airbase. I attended Vajont Elementary School. The other two were Pordenone to the south west, and one in Aviano on a smaller installation away from the air base. Mine was a plainly styled concrete building with three main sections, a gym on its backside, and a playground behind it. On the other side of the fence bordering our playground was a local Italian primary school with similarly aged kids. We didn’t interact with them much except to play annual soccer tournaments and eat pizza with anchovies. I was shuttled on inconspicuous contracted city buses to school, catching it along a predetermined route that wound its way throughout the Friulian townships and countryside.

Dad worked munitions, so when he wasn’t working nights he would drive my sister and me to the bus stop near an Agip station. There an inconspicuous tour-bus would pick us up and take us winding through the towns and across the bridge spanning the great riverbed to school. Vajont today is descendant from the refuge remains of the former Vajont that was completely destroyed in a devastating landslide in the 1960s north of Monte Fara, in the mountain-lake country. The Italian government, gathering the few survivors, built dwellings and a township on the southern outskirts of Maniago safely in between the two riverbeds of the Torrente and away from any dubious mountainsides.

The school is drab and dated, made from a rough dark grey concrete with flakes of black and white pebbles. There was a small playground in the front, but only for kindergartners, and I started there as a first-grader so my playground was in the back with all the other kids. As my dad and I approached the town years later, I began to feel the relief of a nostalgic itch finally being scratched. As it happened, a few army Chinook helicopters were dropping paratroopers in a nearby field as we arrived.

We pulled up to the building with Chinooks beating the air into submission several miles away. I noticed that the school’s front gate was left unlocked, and the structure was clearly unoccupied with no one in sight. After briefly consulting with my dad, we decided that given how far we had traveled, a further investigation of the building was needed. I walked through the gate and was immediately reminded of a scene from my second grade, lining up out in front of the school in the small gravel courtyard. We huddled in puffy coats exhaling visibly and passing red, blue, and yellow plastic cartridges back and forth—I didn’t lend out my Blue Version very often though.

I approached the front door and found it unlocked and slightly ajar. The window was opaque and offered no view inside. I slowly opened it to peer into what-was-then the main lobby leading to the kitchen, gym, and first grade hallway. Inside I found the lobby adorned with canvases and easels. Buckets of color lined the floors and the smell of paint was strong. Before I could reach any conclusions as to the building’s new use, a middle-aged Italian woman approached me from the first-grade hallway. She was wearing a paint-smeared apron and seemed surprised but greeted me warmly. In a very broken and unpracticed attempt at Italian, I asked if she spoke English, and if it was okay to be in the building. She replied in fluent English that the building was recently used as a temporary art gallery and studio. Acknowledging this, I informed her of my status as a former student and her response seemed to suggest that I hadn’t been the first to return.

Soon into our conversation, a younger woman descended smiling out of the same hallway. I don’t think her Inglese was as comprehensive as her mother’s (I’m assuming), but a brief exchange between the three put us all on the same page. The older woman explained that they had been using the building as an art gallery and studio, making huge banners for town parades. Indeed as we walked to the right and into my old hallway, I saw a huge banner on the floor depicting a familiar scene from Italian folklore: a whale devouring a small ship with a flailing boy and a scrambling old man. What’s strangely coincidental is that I first learned of the tale of Pinocchio in a classroom in that same hallway.

I walked into my old first grade classroom stepping over upturned floor and fallen ceiling tiles. The cubbies where I’d keep my belongings were still there, as well as the exact hooks I hung my bag. The room itself was seemingly picked apart in a hurry, the board gone, the windows left dirtied. I could see light-shadows left from posters that had once been plastered on the wall. The other classrooms were more or less the same. The room that once housed the server and computer lab had hundreds of feet of Ethernet cable spooling out of the floor. I found a stack of 5 ¼” floppy disks in a box near the door which I thought was weird—what was on them I wonder?

Aviano 2000 and September 2001

The Elementary was K-6. I was in fourth grade and my sister in first when 9/11 occurred, and our school-day had already concluded when we heard the news. In the following weeks the building went into lockdown fairly quickly. We had European contracted security guards walking around with handguns holstered, but they were friendly and would even play dodgeball with us during recess sometimes. We also had a ton of cameras installed and were subjected to more and more bomb, shooter, and fire drills.

By the end of fourth grade, the school in Vajont, as well as the other in Pordenone and the small one on Area-1 in Aviano were being consolidated into an on-base K-12 school. The new school was huge and yellow and had these great big windows in the library with a southward facing view. The view of course was obstructed by 200-plus square feet of blast netting. Sometimes I’d sit and read books and watch the blast net sway with the window ajar. Ironically, there was an actual attack on the airbase in the early 90s that involved both gunfire and grenades, however no precautions such as private security or blast netting was used following that incident.

It is worth mentioning that the plans to construct the monolithic K-12 on base school had been in motion for many years prior to 9/11. This project, called “Aviano 2000,” had been in full swing since 1994. Based on my impressions of the installation by 2013, this project was still very much in progress (Despite the project apparently being finished in 2009). But that new school sure got finished fast! I managed to dig up an old PDF on the DODEA website regarding the school there, it’s less than two pages.

Vajont circa 2013 was undisturbed for the most part. You always feel huge walking around your childhood jungle gym, and I definitely had that sensation many times during my brief return. It’s easy to see how the turmoil of the early 00s quickly altered the military’s policy toward children’s education. I remember the contests to name the mascot for our new and huge on-base school, us Vajont Vipers ended up calling the middle school the Aviano Patriots, and the Elementary became the Eagles. It goes without saying that the school colors for both the elementary and junior high were red, white, and blue. Even at the time though I felt that this was pretty reactionary and if anything an uncreative attempt to get kids to eventually graduate and join the service.

Before, the schools didn’t strike me as being avenues toward enlistment, I’m sure plenty of graduates did that by virtue of their exposure to that lifestyle, but it wasn’t overtly obvious until those towers collapsed in New York. Now through the power of the online dossier service called Facebook, I see all of these fellow classmates graduated, enlisted, and having tons of babies. To me, this whole scene of memory is like an old continent I left years ago, because the Air Force simply told us to. What’s left feels “old world” but going back put the “new world” in a very intriguing perspective.

What Remains

Many of the restaurants are closed, the owners of those that remain talk of economic downturns on a scale not seen for a generation. The villages and towns are quiet, and the GIs on base feel more isolated from the local life now that housing and schooling are centralized. Before returning to what I jokingly call “the old country,” I had this preconceived notion that being back would reaffirm my nostalgic stupor. I always knew I’d probably end up going back and that doing so would somehow make me a happier person. Like having that dream you’ve always dreamt of having. But seeing it again, as much as it bought me deep pleasure, gave me a new understanding of nostalgia and its clouding influence on one’s desires. What I missed is not merely a product of the passage of time, it was wiped from existence by forces at very high echelons.

The school, the community it fostered, and the locals we comingled with, are lost to that fateful autumn of 2001. We all knew the school’s days were numbered before 9/11, but after the attack, the move to consolidate the students was rapidly accelerated. To think that it was somehow a “better time” or a “simpler time” only occluded the geopolitical-military policies that was its eventual undoing. To my surprise, going back wasn’t like stepping back in time, it was like stepping into an abandoned museum. My experience in the past is relatable to that moment, but forever anachronistic. The painter in the school captured this sentiment well. I feel like the wooden boy turned flesh where, having been consumed and regurgitated by the whale of reality, I was left grappling with a real understanding of what had sailed away into fragments of bureaucratic past and personal memory.